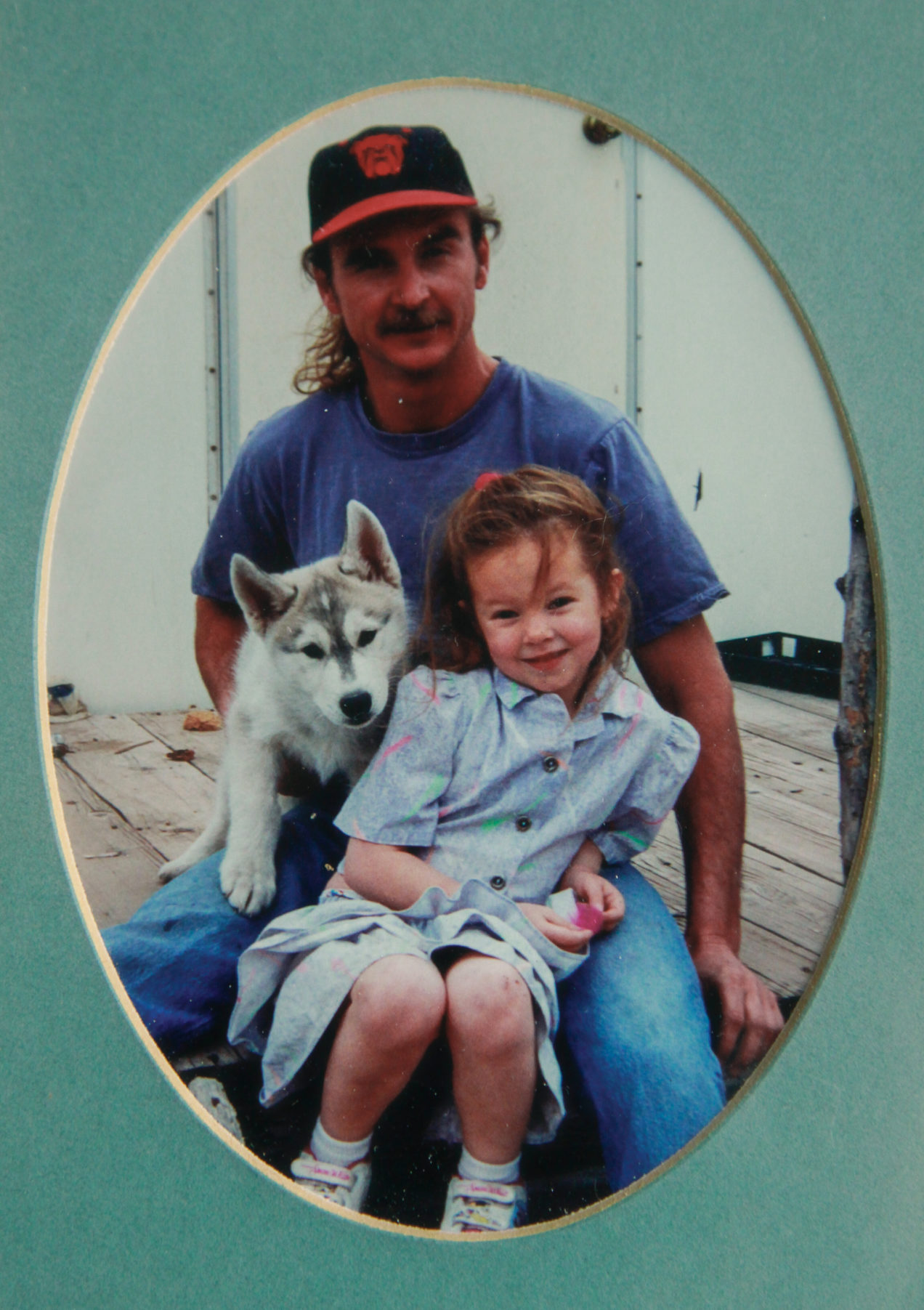

I know I’ve got daddy issues, knew it since I first heard the phrase and thought, Yep, probably me. It didn’t manifest in the usual way, but it did manifest. I was one of a handful sobbing through the father-daughter duet in the Adam’s Family on Broadway. I was the only person in the theater crying through the end of The Place Beyond the Pines as the son, doomed to repeat his father’s mistakes, roared into the sunset on the back of a dirt bike. My daddy issues involve motorcycles. I used to ride dirt bikes. Other non-theater related things manifested as well, but it’s not fair to call them issues. I have had overwhelmingly positive traits, habits, and opinions formed too, and I lay most of these at the feet of my stepdad, the man who raised me, and who I consider to be my father.

My mom usually woke me up by shouting, “TIME TO WAKE UUUUUP!” so I knew it was serious when she sat on the edge of my bed one morning and asked if I’d like to change my last name to Dougherty, and be officially adopted.

I don’t remember how old I was, but I know I thought spelling was generally absurd. I’d just discovered Wade was spelled with an e at the end for no reason, which led to me calling him “Wadey” for years. His last name was particularly problematic. There were at least four unnecessary letters in there — why not spell it Doorty and be done with it? Ellison was a name I could handle — sure, there was that extra l, but it didn’t trip up your mouth, and I’d been spelling it for ages already.

I also didn’t understand that names had context, meaning, power. Every name was completely arbitrary at that time, from chair to Washington. They were just sounds we’d attached meaning to and then came up with absurd ways of spelling. I called my biological father “Dad,” but I might as well have been calling him “Scandinavia.” It was exceedingly weird other people did not call him dad too. Someone recently pointed out that, to this day, I still refer to my mom like “Mom” is her name, because it is her name and why does everyone have to have so many damn names anyway! Just pick one! (I’m looking at you, Slavs.) (And the entire Lacy family for that matter, with your secret names all over the place.)

I asked Mom what that would mean and she said something like, “You and Wade would have the same last name.” But she wouldn’t, would she? Wouldn’t that make her the odd man out? Her last name wasn’t Ellison or Dougherty, it was Lacy. I didn’t mind each of us having different last names. Actually, I thought it was cool. We were each unique individuals, as opposed to other families, who were a homogenous mass, variations on the same theme. If we had to change our names to something, the obvious choice was Lacy, since it was the only option spelled properly.

I didn’t yet understand how name meant legacy, that your name carried with it decades if not centuries of pride and effort and culture and love, that choosing a name was like choosing my own history. I’ve chosen since then — when people ask about my grandfather I tell them about Noel Dougherty, a man I had extreme love and respect for, a cowboy and sheriff and kind, honorable man. All I know about my dad’s dad is that he was violent and died young. But when Mom asked me to make this choice, I thought about it for about thirty seconds, then gave the child Shannon’s version of:

I’ve thought about that decision ever since, more the older I get and the more I understand about the world. Were there times Wade had to defend himself to strangers who didn’t believe he had a real claim on me? Did he ever get smug, knowing looks from people when they realized he wasn’t my ‘real’ dad? Did he ever have to bare suspicion from a well-meaning stranger who thought that my mom was ‘safer,’ that he likely hadn’t been around very long, that he didn’t care as much? Did the Dougherty family use step-daughter more often than daughter when describing me? Was there a hidden defensiveness when introducing me as his daughter, because step-daughter was just too impersonal, implied too much distance?

Worst of all, did he wonder, even fleetingly, that I had made a choice and it hadn’t been him? That a part of me felt I was just stuck with him, and there was some magic place in my heart he’d never access, a part specially reserved for my biological father?

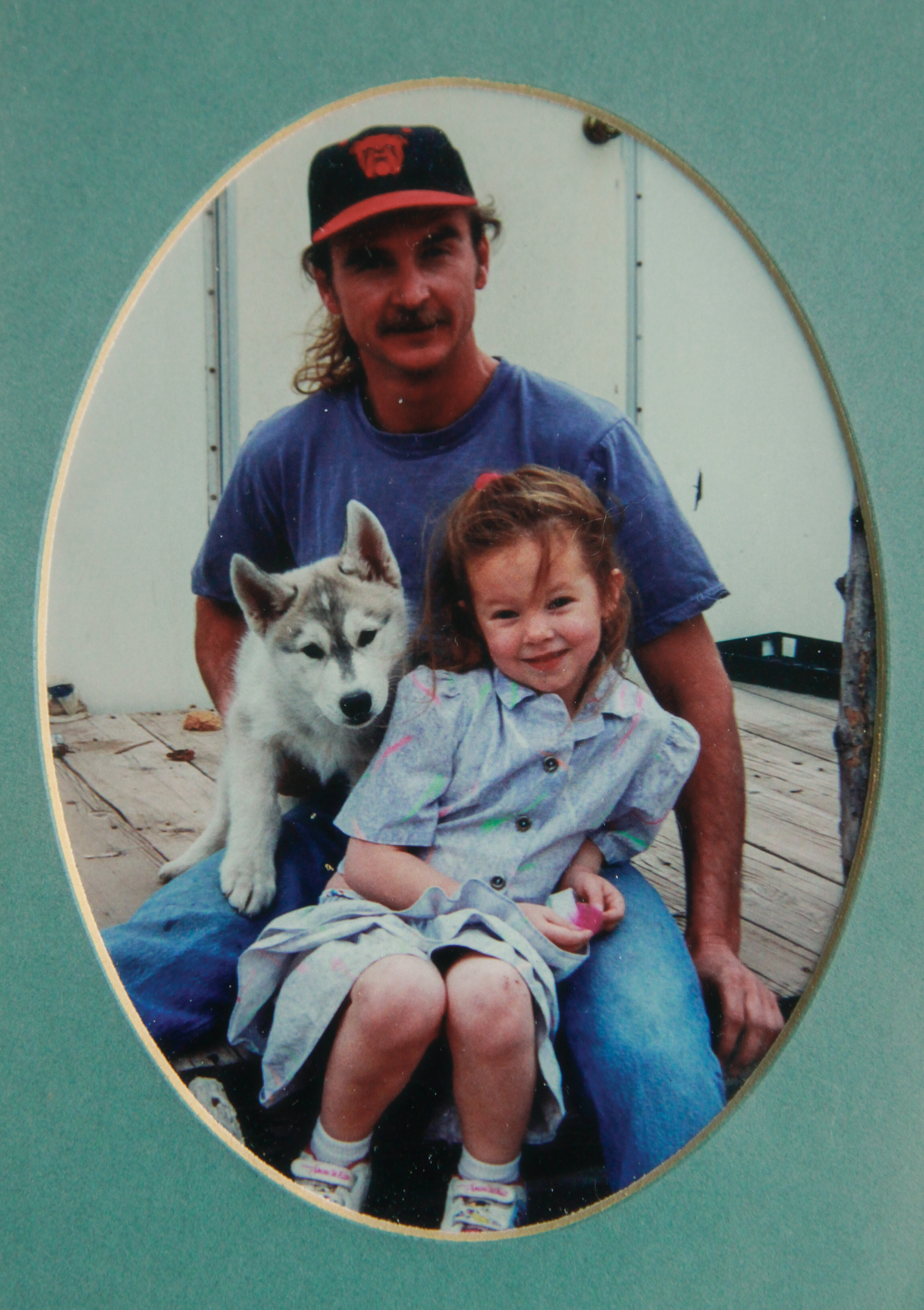

This KILLS ME. I have no memories before Wade was in my life. He could’ve personally given birth to me, it’s not like I remember one way or the other. Wade and I were really close growing up. I always had his full attention. He never told me anything was a bad idea (and I had a lot of ideas) — he just said, “Let’s see if we can make nunchucks ourselves — here, this is how you use a staple gun.” If I ever got that look from someone wondering why I’d called my dad by his first name, or why we had different last names, I was the one who got aggressive. I’ve probably said, “He raised me! Since I was five!” a hundred times.

At some point I tried to make clear he was the one I chose, he was the one I loved, he was the one I wanted. Mom and I went to Hobby Lobby and I got him a plaque with a boy and a black lab fishing and the words: Anyone can be a father. It takes someone special to be a dad.

This was super difficult for me. It caught the sentiment I was going for but the titles were all wrong and I was not a boy and I thought fishing was boring. What if he thought it meant the opposite of what I meant? I still called Dad dad, but that was just his name! Better if it’d been two dirt bikers painted on a plaque, one tall, one short, with the words: Anyone can be a dad. It takes someone special to be a Wadey.

I am an intently impatient person. I am painfully aware of my finite life, and how much time I have to do what I want to do. This made me miserable as soon as I wasn’t hustling as hard as I possibly could, namely after I graduated and was trapped in a fulltime job that made me feel like dying in slow motion. I’m learning to enjoy life again, in a deeper, more meaningful way, and a big part of that is figuring out why I am this way.

I used to think it was run-of-the-mill fear of death, but that never sat right. You’re not going to know you’re dead, right, so what does it matter? I’m really motivated to have the life I want, but chasing the carrot doesn’t make you panic if things fall behind schedule, doesn’t make standing in line with nothing useful to do make you sweat, make you nauseous, make you feel worse than death — trapped. Wasted time gives me claustrophobia. That isn’t from desperately wanting anything. That is from fear — fear with a ticking clock.

I think I’ve figured it out. If fear of my own death is a summer breeze, fear of someone I love dying is a hurricane on Jupiter. When Naz and I were dating long-distance I refused to ever be the one to hang up, because if he died, I’d never get over clicking that red button. I sometimes tell people before as they’re leaving, “Don’t die!” It is not a joke. My nightmares are of trying to protect my friends and family (usually through the apocalypse, and often with zombies) and failing. I used to hold Bubbles the cat and whisper to her, “Please don’t die, please live forever,” over and over again until I fell asleep. (She’s now nineteen and still going strong.)

Told you. Hurricane on Jupiter.

Wade smokes. A lot. Before he started smoking, he chewed tobacco — he once told me he started chewing when he was twelve years old. He’s turns 55 today. I know smoking kills. I also know quitting cigarettes is as difficult as quitting heroin, and that it’s not just about willpower. It takes willpower and a whole rearranging of your day and your life with huge support of everyone around you and treating it as much like a sickness as any heroin addiction. Tobacco catches you, with its little whispers, “It’s not that bad, you’re not addicted, you just feel like having a quick smoke right now, you can always stop if you really wanted to.” I don’t blame Wade for anything, and especially not for staying enslaved to the drug that caught him as a child.

But I do think it’s going to kill him. His death is my sense of urgency. I want to make him proud. I want to buy him and Mom a fancy ranch soon enough they have time to enjoy it. I want him to meet my children, and not just meet them, but help raise them, because if there’s one thing Wade’s really, really good at, it’s raising kids. How much longer do I have? What do you think? Twenty-five years, my lifetime once over again? Fifteen? Five?

It’s taken me a long, long time to work up the courage to write this. I guess that’s why they’re called issues.

I love you, Wade, and miss you terribly. Happy birthday.